|

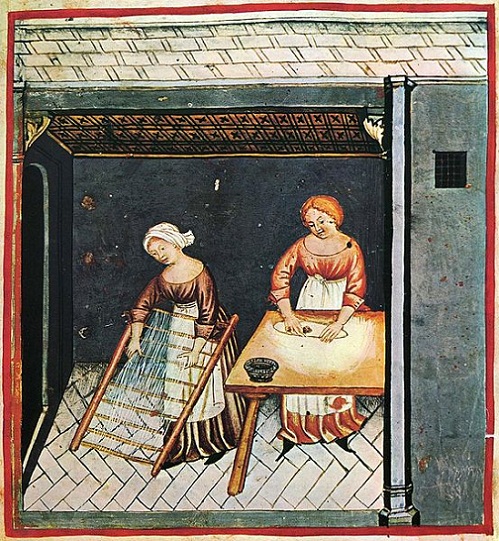

The art, culture and folklore of pasta is a complex topic. While talking and writing about it isn’t as terrific as eating it, it’s a lot of fun. And no, Marco Polo didn’t bring it back from China. That story was part of a 1929 promotion instigated by the National Macaroni Manufacturers Association, a U.S. organization. Then Hollywood got into the act. In the 1938 movie, The Adventures of Marco Polo, Gary Cooper’s Polo asked a Chinese man with a bowl of noodles what it was. The man replied that it was spa-get. No kidding. Chinese archeological finds confirm four thousand year old remnants of pastas made with millet flour. Yet it was apparently unknown in Roman era kitchens. Nevertheless, pasta was known in both China and Italy long before Polo took his first step eastward. Food historians believe that an early form of pasta arrived in Sicily with the Moors and the Arab spice traders and it traveled north through the peninsula. Another myth attributes the introduction of dried pasta to the Americas to Thomas Jefferson. Brilliant as he was, this is romantic fiction. Pasta arrived in North America compliments of the British. It predates the great human migrations from Italy by a couple of centuries. By the Civil War, macaroni was being mass-produced and was economically available to working class Americans. Unfortunately, we didn’t do a lot with it. Near the end of the 19th century, Franco-American began selling canned spaghetti claiming it was made from a French recipe. I feel certain that the Italians would be happy to leave the credit for that to the French. As an April Fool’s stunt, the somber BBC once broadcasted a television program in which it portrayed Italian farmers tending spaghetti vines, harvesting them by hand, drying the long strands in the sun and then dropping them in boiling water. Let’s face it. If there is anything important about all this, it is what the Italians did and continue to do with it. While pasta may be known in many cultures, only Italy developed a full-fledged, world-class cuisine around it. That is only one of their culinary contributions. Within their borders, Italy has documented 310 specific forms of pasta known by more than 1,300 names. Pasta is made fresh, dried, die cut, sheet cut, rolled. Once the form is determined, it can be stuffed, filled, boiled or baked. It is an art form. So why all those shapes, sizes, twists, turns, swirls and curls? It turns out there’s a bunch of good reasons. Both shape and texture count. The slender light stands of angel’s hair, fidelini, spaghetti, and vermicelli are best for conveying lightly creamy sauces such as pestos and perhaps a creamy lemon sauce. For heavier vegetable based sauces, especially for broccoli, the thicker bucatini, linguine, tagliatelle and fettuccine are better prepared for the job. Meat and thicker, chunkier sauces need all the little nooks and crannies of fusili, penne, rigatoni, shells, farfalle, radiatore and ditalini to trap those lovely little bits. For the thickest and densest dishes there are the tortellini, ravioli and agnolotti for stuffing and the cannelloni and lasagne for filling and layering. There are customs and then there are rules. One such “rule” is that it is considered quasi-criminal in Italy to sprinkle cheese on a seafood pasta dish. In columns past we have offered many pasta dishes, including Beet Purple Pasta, Pasta with Asparagus, Lemon and Goat Cheese, Caulifower Pasta, Fettuccini Alla Zucca, Mercato Profuso, Broccoli, Saffron and Raisin Pasta, Capelli with Arugula, Tagliatelle with Peas, Pea Shoots and Lettuce and Pear, Mascapone and Pecorino Fettuccini. All of which are available on the web site. Today’s offering is a light fresh dish with a bit of crunch, Linguine with Snow Peas, Chives and a Creamy Lemon Sauce.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |